A big investor, who is seeking a board seat, opposes Jes

Staley's global ambitions

By Margot Patrick

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (May 2, 2019).

Jes Staley runs one of the last full-service banks left in

Europe that compete with Wall Street. The way the 62-year-old

American banker sees it, his restructuring of U.K.-based Barclays

PLC has primed it to take on the likes of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

and Morgan Stanley.

British-born investor Edward Bramson couldn't agree less, and

his New York firm has bought a sizable stake in Barclays. He is

trying to force the bank to scale back its Wall Street ambitions,

to become a consumer and commercial lender with smaller

investment-banking operations.

So far, Mr. Staley, the chief executive, is having none of it.

"He wants us to retreat into a foxhole? He should go back to

Connecticut," Mr. Staley has told colleagues, referring to the

state where Mr. Bramson has a home and raises horses.

The fight over the future of Barclays will help determine

whether any of Europe's banks can retain global ambitions.

For centuries, the U.K. was synonymous with international

banking, and London was the first stop for companies and

governments looking to raise money. Then its banks ventured

overseas to grab a greater share of lending and trading, bringing

some of them close to death during the financial crisis a decade

ago.

Today, U.S. banks dominate fundraising and trading, buoyed by

healthier balance sheets and robust American capital markets.

Mr. Staley has a vision for Barclays, which absorbed much of

Lehman Brothers after its collapse. He wants it to become a compact

version of JPMorgan Chase & Co. -- the bank where he spent more

than three decades of his career.

Making that happen hasn't been easy. The bank's share of global

investment-banking revenue has risen a couple of notches, but

returns on capital for the unit are below targets and the stock

price has declined. Mr. Staley recently forced out the head of the

investment bank and took the reins himself.

Mr. Staley said last week the bank has no intention of changing

course. "We like the progress we're making in the corporate and

investment bank....And we're going to continue with the strategy we

set out three years ago."

By refusing to retreat, Mr. Staley is going against the grain in

Europe. Stock valuations rose at UBS Group AG and Credit Suisse

Group AG after they decided to narrow their focus several years

ago.

Mr. Bramson's investment firm, Sherborne Investors, in a letter

to Barclay's shareholders in early April, pressed its case for a

strategic reversal. It argued that in the post-financial-crisis

world only the biggest American banks are in a position to offer

the full suite of investment-banking products.

"We believe that the current strategy is untenable in the long

run," the letter said.

Mr. Bramson, 68, has demanded a seat on Barclays's board of

directors. Shareholders are scheduled to vote on that resolution on

Thursday. While few Barclays shareholders have said they would vote

for him, many have expressed frustration with the share price.

Mr. Bramson has succeeded before in getting his nominees elected

to boards that have dismissed his calls for change. In its recent

letter to Barclays shareholders, Sherborne said Mr. Bramson has

"significant insight" to contribute and could be a stabilizing

influence on the bank.

In its own letter to shareholders in April, the Barclays board

said it strongly opposes him joining, calling his style "disruptive

and uncollaborative."

There have been three meetings between Messrs. Staley and

Bramson and their respective teams. All have been cordial, but none

have led to any action. "We come, we give the briefing and we get

no feedback," said one person in the Barclays camp.

In a meeting last spring, Barclays board member Crawford Gillies

told Mr. Bramson that the bank's first-half earnings would be

strong enough to quell any strategy doubts, according to a person

familiar with the discussion. The market won't care, Mr. Bramson

replied.

Barclays beat analysts' estimates for that period, but its

shares continued to slide, as Mr. Bramson had predicted.

Barclays says other factors are weighing on its share price,

such as Britain's planned departure from the European Union and

persistently low interest rates that hamper returns across the

banking industry.

Last September, Mr. Bramson wrote to the Barclays board asking

for a seat. A meeting with Mr. Bramson in November left Mr. Staley

frustrated that Mr. Bramson was creating uncertainty around the

Barclays stock but had said little about how he wanted to change

Barclays, according to one person familiar with the discussion.

What should we be doing differently? Mr. Staley asked at one

point, holding up his hands, according to the person familiar with

the discussion. Mr. Bramson didn't reply. Shortly after the

meeting, the chairman told Mr. Bramson he wasn't wanted on the

board.

The struggle over the soul of Barclays has been going on since

U.K. financial markets deregulated in the 1980s, fueling the

ambitions of British banks to be global players in securities

trading and corporate advice. A succession of CEOs pulled Barclays

back and forth between expansion in that area and retreat.

Former CEO Bob Diamond, also an American, supplied Barclays with

a key to competing with Wall Street on its home turf by buying

parts of Lehman Brothers during the financial crisis. Mr. Staley

was a top pick to succeed him, but the job went instead to a

Barclays retail banker who took an ax to the investment bank over

three years and saw the share price rise 50%.

Mr. Staley got a second shot at the top job in December 2015.

Informed by his long career at JPMorgan, he saw a chance for

Barclays to emulate the American giant with a balance of consumer,

commercial and investment banking -- a range of services that spans

credit cards in Germany and private banking in India.

Mr. Staley had left JPMorgan after concluding he wouldn't

succeed CEO James Dimon. He hired around 30 senior staffers from

JPMorgan, prompting Mr. Dimon to call the Barclays chairman to ask

Mr. Staley to stop.

Mr. Staley has said that Barclays should be the first choice for

companies that don't want to rely solely on U.S. lenders or

advisers. "The fact that we are a non-American firm in the U.S.

capital markets dominated by American players, we're a very healthy

diversifying counterparty," he said during a news conference in

February. Walking away from the investment bank, he said, "would

just be irresponsible."

In March, he ousted the head of the investment bank, Tim

Throsby, a former JPMorgan executive he had picked to lead it. Mr.

Staley took direct command of the operation, acknowledging its

performance is "not yet where we need it to be."

Analysts expect the bank this year to make a 8.2% return on

tangible equity, a measure of profitability, well below Mr.

Staley's stated 9% target. JPMorgan's figure was 17% last year.

Sherborne's Mr. Bramson, who was born in England to an American

mother, left Britain 40 years ago to work in private equity in New

York. He contends that Barclays's trading businesses -- it makes

markets for customers in stocks, bonds and derivatives -- rely too

much on trading activity by fickle clients such as hedge funds and

other money managers. He says competing successfully in the space

requires a strong roster of corporate clients, as JPMorgan and

Citigroup Inc. have, or wealth-management arms, as UBS and Credit

Suisse have.

Sherborne entered the fray after it raised GBP700 million ($913

million) for a new investment. Some of its investors had backed Mr.

Bramson when he gained board seats and pushed successfully for

turnarounds at investment companies F&C Asset Management PLC

and Electra Private Equity.

Mr. Bramson and his team thought Barclays shares looked

inexpensive at less than GBP2, according to people familiar with

their strategy. They saw a chance to get the bank to improve its

low return on equity by reallocating capital away from the

investment bank, much as UBS had done. They believed that would

unlock the value of Barclays's U.K. retail bank, one of the best in

the country.

In March 2018, Sherborne disclosed it had a 5.2% stake in

Barclays, which has since increased to 5.5%.

Barclays braced itself for a critique of its business,

assembling an internal team and hiring outside advisers. For

months, Mr. Bramson gave little indication about what he wanted,

beyond a turnaround.

Last summer, Mr. Bramson told the Barclays board he wanted to

help it find a successor to Chairman John McFarlane, who is

retiring in May. Barclays ignored the request and made its own

selection.

Some Barclays shareholders say they don't see how Mr. Bramson

could have a better solution than Mr. Staley's management team. "We

don't think that Bramson's answer is the right one because we don't

think you could seamlessly and painlessly extricate billions in

capital from the investment bank," says Richard Buxton, head of

U.K. equities at Merian Global Investors.

In December, Mr. Bramson told Sherborne's investors in a letter

that he had lost confidence in continuing discussions with Barclays

because it wouldn't acknowledge its strategy wasn't working.

In February, Sherborne applied for the shareholder vote on

whether Mr. Bramson should get a board seat. In March, it extended

the financing for its Barclays stake into 2021, according to a

securities filing, suggesting it is in for the long haul.

Barclays shares have fallen roughly 8% since Sherborne started

buying. In meetings with Barclays shareholders and others, Mr.

Bramson's criticism has been pointed, according to people who have

met with him.

He has questioned the experience of Barclays board members and

their resistance to considering opposing points of view. The

faltering share price, he has said, even as earnings have improved,

underlined his view that investors don't support the strategy.

The Barclays board, in its letter to shareholders in April, said

it "recognizes that Barclays does not yet perform at the level at

which it should," but that "another strategic overhaul is not what

Barclays needs right now."

--Max Colchester contributed to this article.

Write to Margot Patrick at margot.patrick@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 02, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

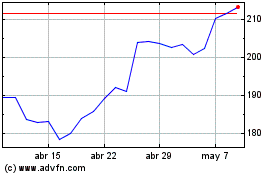

Barclays (LSE:BARC)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

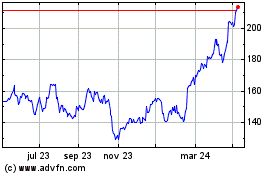

Barclays (LSE:BARC)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024