By Marc Benioff

I first met Steve Jobs in 1984 when Apple Inc. hired me as a

summer intern.

The fact that I'd landed this gig in the first place was

something of a fluke; as a college student at the University of

Southern California, I'd reached out to the company's Macintosh

team to complain about a bug in its software and somehow parlayed

that conversation into a job. While I'd done my best to impersonate

a seasoned developer, at 19 years old, the sum total of my

programming experience was writing a dozen arcade and adventure

games in high school. Working at Apple was the big leagues, and

while I felt profoundly underqualified, nobody tossed me out the

door that summer. In fact, every time Steve Jobs passed my cubicle,

I somehow summoned the nerve to strike up a conversation.

It wasn't much, but through those small interactions, a bond

would eventually form. Steve and I shared a love for technology and

science as well as a passion for meditation and Eastern philosophy.

In addition to being a brilliant executive and peerless innovator,

he was a spiritual, intuitive person who had a gift for seeing the

world through many perspectives at once. I saw that he had a

willingness to share his wisdom, and I wasn't afraid to ask for

it.

Even once my internship ended, we stayed in touch, and as my

career progressed he became a mentor of sorts. Which is why, one

memorable day in 2003, I found myself pacing anxiously in the

reception area of Apple's headquarters.

By then, I was CEO of Salesforce, one of the first companies to

deliver enterprise software to customers as a subscription over the

internet. In the four years since Salesforce opened for business,

we'd hired 400 employees, generated more than $50 million in annual

revenue, and were laying the groundwork for an IPO the following

year. We were justifiably proud of our progress, but I'd learned

enough about the technology business to know that pride is a

dangerous state of mind.

Truth be told, I was feeling stuck. To catapult the company into

the next phase of growth, we needed to make a bold move. We'd

survived the scary startup phase where so many companies crash and

burn, but I was struggling to imagine how I'd navigate the pressure

of running a public company that has to lay itself bare to Wall

Street every quarter.

Sometimes seeking guidance from mentors is the only sure way to

survive these bouts of inertia. That is why I decided to make a

pilgrimage to Cupertino, Calif.

As Steve's staff ushered me into Apple's boardroom that day, I

felt a rush of excitement coursing through my jangling nerves. In

that moment, I remembered what it had felt like to be an

inexperienced intern mustering up the courage to say a few words to

the big boss. After several minutes, Steve charged in, predictably

dressed in his standard attire of jeans and a black mock

turtleneck. I hadn't settled on precisely what I wanted to ask him,

but I knew I'd better cut to the chase. He was a busy man, and was

legendary for his directness, and ability to quickly zero in on

what's important.

So I showed him a demo of the Salesforce customer relationship

management service on my laptop and, true to form, he immediately

had some thoughts. After unleashing a torrent of rapid-fire

suggestions on our software's basic functionality, down to the

shape and color of its navigation tabs, Steve sat back, folded his

hands together, and got to the larger point. Salesforce had created

a "fantastic enterprise website, " he told me. But both he and I

knew that that alone wasn't enough.

"Marc," he said. "If you want to be a great CEO, be mindful and

project the future."

I nodded, perhaps a bit disappointed. He'd given me similar

advice before, but he wasn't finished.

Steve then told me we needed to land a big account, and to grow

"10 times in 24 months or you'll be dead." I gulped. Then he said

something less alarming, but more puzzling: We needed an

"application ecosystem."

I understood that to hit the big leagues, we needed a huge

marquee customer win. But what would a Salesforce "application

ecosystem" look like? Steve told me that was up to me to figure

out.

We tripled in size over the next three years, topping $300

million in revenue, but the puzzle posed by Steve remained

unresolved. The more innovative products and features we released,

the more our customers expected from us. Privately, I started to

worry about whether we could cope with the pressures of scaling

up.

In previous eras, a company in our position would have tapped

its most brilliant scientists and squirreled them away behind a

triple-bolted door with top secret painted on it. These appointed

geniuses would have spent long days in isolation, wrenching

together prototypes and puzzling over clay models, walled off from

any ambient noise.

At the end of the process, these scientists would emerge from

their lairs, likely over caffeinated and unkempt, and would wheel

out a gurney containing some new product, the likes of which nobody

had ever seen. Then it was up to customers to determine whether it

was a game changer. Too often, it wasn't.

We had subscribed to this outdated model too, in the early years

of the company. Then, in 2006, the approach to innovation at

Salesforce started to change. To innovate on a truly massive scale,

we realized that we couldn't simply demand more of our already

overworked engineering department. The only possible way to scale

up our innovation efforts was to start recruiting outsiders.

One evening, over dinner in San Francisco, I was struck by an

irresistibly simple idea. What if any developer from anywhere in

the world could create their own application for the Salesforce

platform? And what if we offered to store these apps in an online

directory that allowed any Salesforce user to download them? I

wouldn't say this idea felt entirely comfortable. I'd grown up with

the old view of innovation as something that should happen within

the four walls of our offices. Opening our products to outside

tinkering was akin to giving our intellectual property away. Yet,

at that moment, I knew in my gut that if Salesforce was to become

the new kind of company I wanted it to be, we would need to seek

innovation everywhere.

So I sketched out my idea on a restaurant napkin. And the very

next morning, I went to our legal team and asked them to register

the domain for "AppStore.com" and buy the trademark for "App

Store."

Shortly thereafter, I learned that our customers didn't like the

name "App Store." In fact, they hated it. So I reluctantly conceded

and about a year later, we introduced "AppExchange": the first

business software marketplace of its kind.

These decisions gained added relevance when I returned to

Apple's Cupertino headquarters in 2008 to watch Steve unveil the

company's next great innovation engine: the sprawling, boundaryless

digital hub where millions of customers, developers, and partners

could create their own applications to run on Apple devices. Steve

was a master showman, and this presentation didn't disappoint. At

the climactic moment, he said five words that nearly floored me: "I

give you App Store!"

All of my executives gasped. When I'd met with Steve Jobs in

2003, I already knew he was playing a hundred chess moves ahead of

me. None of us could believe that Steve had landed on the same name

I'd originally proposed for our business software exchange.

For me, it was exciting and humbling. And Steve had unwittingly

given me an incredible opportunity to repay him for the prescient

advice he'd given me five years earlier. After the presentation, I

pulled him aside and told him we owned the domain and trademark for

"App Store" and that we would be happy and honored to sign over the

rights to him for free.

Steve helped me understand that no great innovation in business

ever happens in a vacuum. They're all built on the backs of

hundreds of smaller breakthroughs and insights -- which can come

from literally anywhere. AppExchange now has more than 5,000 apps,

ranging from sales engagement and project management tools to

collaboration aids.

Building an ecosystem is about acknowledging that the next

game-changing innovation may come from a brilliant technologist and

mentor based in Silicon Valley, or it may come from a novice

programmer based halfway around the world. A company seeking to

achieve true scale needs to seek innovation beyond its own four

walls and tap into the entire universe of knowledge and creativity

out there.

From "Trailblazer: The Power of Business as the Greatest

Platform for Change" by Marc Benioff and Monica Langley, to be

published on Oct. 15 in the U.S. by Currency, an imprint of Random

House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, and in the U.K by

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. Copyright (c) 2019 by Salesforce.com,

Inc. Mr. Benioff is the chairman and co-chief executive officer of

Salesforce.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 11, 2019 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

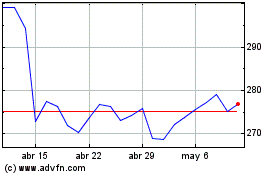

Salesforce (NYSE:CRM)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Salesforce (NYSE:CRM)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024