Liquor maker is lobbying Indian officials to slash taxes,

preempt prohibition

By Saabira Chaudhuri

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 11, 2019).

Johnnie Walker-maker Diageo PLC is betting on India, the world's

largest whiskey market, to power its growth. But first, it has to

win over dozens of local governments that want to either ban liquor

or tax it heavily, even as more Indians embrace drinking.

To protect sales, Diageo is helping a number of Indian states

develop tax policy. To demonstrate that it is a responsible actor,

it is rolling out road-safety programs. Diageo is even presenting

ways that states can move up India's ease-of-doing-business

rankings -- which are important for attracting investment -- by

cutting red tape for alcohol.

Indian society has long viewed alcohol consumption as a sign of

moral laxity. Yet, consumption is soaring. The average Indian drank

38% more alcohol in 2017 than in 2010, according to a study in The

Lancet, a medical journal. The rise is among the world's steepest

and has led to more deaths and diseases attributed to alcohol, up

12% and 9% respectively. Booze has also been blamed for road

accidents and wasted household incomes.

The growing popularity of liquor, along with protests from women

who say alcohol leads to domestic violence, is prompting some

Indian policy makers to act. The state of Andhra Pradesh, which is

home to 50 million people, took over thousands of liquor stores

last month as a first step toward prohibition. In August, the top

court in the hill state of Uttarakhand ordered the government to

ban alcohol.

"Some educated people say that drinking liquor is a fundamental

right. I strongly object," Nitish Kumar, chief minister of Bihar, a

state with 100 million people, said in a recent speech. "There is

data to back the claim that liquor is evil for society." After

Bihar banned alcohol three years ago, Diageo's sales slumped in the

state and it was forced to shut its distilleries there.

Navigating India's volatile regulations is an increasing area of

focus for the world's biggest whiskey maker, especially because it

is counting on the country's burgeoning middle class to offset

slowing drinking in the West. Between 2013 and 2014, Diageo paid

$3.2 billion for a controlling stake in United Spirits Ltd.,

India's largest spirits company. It now generates roughly 60% of

its volume growth from the country.

Other alcohol giants, facing similar headwinds, are also betting

on India. Pernod Ricard SA, which bought Seagram Co.'s India assets

in 2001, has pushed pricey brands like Chivas scotch. Sales are

growing strongly and India is vying with China to be Pernod's

second-largest market behind the U.S. Budweiser brewer

Anheuser-Busch InBev SA and other brewers are also doubling

down.

Still, some executives question whether Diageo can successfully

apply its global mantra -- that alcohol in moderation can be part

of a balanced lifestyle -- to India.

"The alcohol culture in India is totally different to the West,"

said Manish Shyam, who worked in corporate affairs for Diageo until

earlier this year. "It's about bang for your buck, about spending

as little as possible and getting the maximum kick."

Moreover, India is one of the world's toughest places to sell

alcohol. Booze is subject to a complex patchwork of state-by-state

regulations, alcohol advertising is banned and imports are taxed at

150%. Diageo India requires about 200,000 permits and approvals

each year to do business.

Influencing regulation in India is like "trying to break a

rock," said Diageo India head Anand Kripalu at an investor event in

May. "You've got to chip away, chip away and one day it'll

part."

In 2015, Diageo set up a 12-person team to improve the alcohol

industry's reputation and influence policy. It's also working with

the International Spirits and Wines Association of India, an

industry trade body, to forestall damaging regulation.

"The prohibitory message was getting picked up a lot," said Indu

Anand, who worked as Diageo India's head of public policy until

2017. "We had to intervene and come up with programs and projects

to say we encourage responsible drinking."

Taxes are a key focus. Alcohol is one of the few industries that

states have been able to tax directly since 2017, prompting states

to raise taxes on booze to generate revenue and discourage

consumption.

In response, ISWAI, the trade body, is holding workshops to

"co-create" mutually beneficial tax policy for imported brands with

excise officials. Its argument: Lower taxes boost demand and

generate higher tax revenue.

That effort secured a 30% price cut for Johnnie Walker Black

Label last year in Karnataka, the state that's home to Bangalore.

Volumes jumped 64% in the five months after the move, a success

story that's now being used to convince regulators elsewhere.

Volumes of Pernod's Chivas brand jumped 332% after taxes fell

28%.

"My message to everyone is it's not a Pernod versus Diageo

fight. It is everybody versus the government," said Amrit Kiran

Singh, who runs ISWAI.

The World Health Organization says high taxes are among the most

effective tools to curb binge drinking, and many public health

researchers are wary of the industry's efforts to influence tax

policy and public-health interventions. "You become the policeman

as well as the thief," said Vivek Benegal, professor of psychiatry

at the Bangalore-based National Institute of Mental Health and

Neurosciences.

In 2017, India's Supreme Court banned the sale of booze at

shops, bars, restaurants and hotels within 500 meters (547 yards)

of national and state highways in a bid to reduce road accidents.

The move contributed to Diageo's sales falling by more than half

during that fiscal year.

To prevent further restrictions, Diageo is funding programs

endorsed by the transport ministry that it says are designed to

improve road safety and encourage responsible drinking. The

ministry is relying on Diageo to educate university students

applying for driver's licenses about the dangers of speeding, not

wearing helmets and driving drunk.

Harman Singh Sidhu, a road-crash victim turned campaigner whose

2012 petition led to the highway liquor ban, said industry efforts

to curb drunken driving pale in comparison with advertising that

encourages drinking. While alcohol ads are banned on TV and in

print, brands advertise heavily on social media. They also sell

booze-branded products such as bottled water, soda and playing

cards that generate little revenue but serve as effective marketing

tools.

"As far as India is concerned, we are in the lap of the

industry," Mr. Sidhu said.

Write to Saabira Chaudhuri at saabira.chaudhuri@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 11, 2019 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

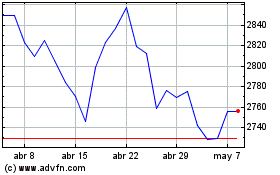

Diageo (LSE:DGE)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Diageo (LSE:DGE)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024