Ex-managers spread its scrappy mentality, leaving harsher parts

of the culture behind

By Dana Mattioli

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 21, 2019).

Latchel Inc. is a 3-year-old, 20-person startup in Seattle that

sells home-maintenance services. It has something in common with

its enormous neighbor Amazon.com Inc., specifically, 14 leadership

principles, many of which are identical.

That's not a coincidence. Will Gordon, a Latchel co-founder,

worked for the e-commerce giant for nearly three years. And like

many former Amazon executives, Mr. Gordon took with him its

management style -- including principles such as "customer

obsession" and "bias for action" -- when he left a few years ago.

He's part of the diaspora of Amazon alumni spreading the business

gospel of Jeff Bezos across the corporate world.

For decades, General Electric Co. was America's breeding ground

for corporate chiefs. Executives who rose through the

conglomerate's ranks in its heyday and passed through its rigorous

management program went on to run behemoths such as Home Depot Inc.

and 3M Co.

In the Big Tech era, Amazon has become the incubator for CEOs

and entrepreneurs. At the core of Amazon's ethos is a scrappy

startup mentality that encourages employees to constantly innovate

and challenge the way things are typically done.

There's one element some ex-Amazonians are leaving behind: the

harsher parts of Amazon's culture, such as hiring practices that

favor skills over collegiality.

Amazon is known for disregarding social cohesion in interviewing

candidates, former employees said, elevating other traits over an

ability to work well with colleagues. Mr. Gordon of Latchel

originally embraced that tenet.

"We approached hiring this way and it was a big, big mistake,"

he said. He had to fire one employee he had hired who was capable

but couldn't get along with the team. "We need social cohesion and

to like each other because we have to put in lots of additional

hours and time because it's a startup," Mr. Gordon said.

An Amazon spokesman said that social cohesion is balanced by

Amazon's "earn trust" leadership principle, which says that

"leaders listen attentively, speak candidly, and treat others

respectfully."

Alums of the Seattle-based giant, which employs over 750,000

people, head companies including Tableau Software Inc., Zulily

Inc., Groupon Inc., and Simple, an online banking unit of Banco

Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA.

The company Mr. Bezos founded in his garage 25 years ago has

also spawned a legion of startup founders, who run or have run

companies as varied as content-streaming site Hulu, e-commerce

platform Verishop Inc., cannabis hub Leafly Holdings Inc., and

trucking-software maker Convoy Inc. And when directors of troubled

property-leasing startup We Co. ousted their leader, they tapped an

ex-Amazon executive as co-CEO to try to stabilize the

situation.

Business leaders often incorporate lessons learned in past

positions at other companies. Amazon's management culture is

especially well-defined and hammered endlessly into its executives,

say those who have worked there.

In addition to its 14 leadership principles, there are more

general practices that are aimed at keeping teams nimble and that

let data guide business decisions. Cross-functional teams should be

small enough that two pizzas would suffice for dinner. Many

meetings start with 30 minutes of silence as everyone reads the

same six-page document. Employees pitching new products create

fictional press releases to focus on the benefits to customers.

(See below for a list of the 14 principles.)

Former employees say some of the aspects of company culture

they're leaving behind include an intense pace and a preference for

blunt confrontation that can cause some employees to burn out.

Amazon has also faced criticism from some customers and sellers

that it has allowed shoddy or dangerous merchandise on its platform

in its pursuit of rapid growth.

An Amazon spokesman said that safety is important, and that

"third-party sellers are required to comply with all relevant laws

and regulations when listing items for sale in our stores. When

sellers don't comply with our terms, we work quickly to take action

on behalf of customers."

Jeff Yurcisin, a 14-year veteran of Amazon who last year became

president of Zulily, an e-commerce company focused on flash sales,

said he has brought the tech giant's approach to hiring. Every

interviewer now asks a candidate questions based on a specific

skill related to the role.

But Mr. Yurcisin said he is striving for a "more empathetic

culture" at Zulily. "Over 25 years, Amazon has rewarded direct

communication and incredibly high standards, which taken to an

extreme, can be off-putting to some employees who can take it

personally," he said. Ultimately, he added, "trying to replicate

their culture is not a recipe for success."

"I really like our culture," said Jeff Wilke, the CEO of

Amazon's consumer business. "It's not for everyone. There are lots

of ways to build a culture, there are lots of kinds of cultures,

and, you know, people certainly are free to sample and say,

'Actually, you know, this one's not for me.' "

Looming over Amazon's culture is Mr. Bezos, one of the world's

richest men. Jack Welch's two decades as CEO and chairman of GE

infused that company with Welchisms such as "fix, close or sell,"

and an employee ranking system that systematically cut its lowest

performers. When Mr. Welch stepped down, his progeny headed up more

than a dozen companies and GE's employee base was a favorite mining

ground for executive recruiters. Mr. Welch declined to comment.

With Amazon's ascent to one of the world's biggest companies,

Mr. Bezos has become a management guru, with management students

poring over his annual shareholder letter, much like how investors

study letters from Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Chairman Warren

Buffett.

Mr. Bezos trumpets a philosophy that "it's always Day 1 at

Amazon," urging employees to never stop innovating or become

complacent. In essence, the idea is to keep his $870 billion

company, the U.S.'s second-biggest private employer, acting like a

startup.

In the early 2000s, Mr. Bezos inspired one of the more famous

Amazon organizational tools: The narrative, or "six-pager" in

Amazon parlance, a document that a team of employees writes when

proposing an idea.

It originated during a frustrating PowerPoint presentation where

Amazon's management team found themselves scribbling in the margins

of the deck being presented to better process it, said Mr. Wilke.

When the speaker asked if the team needed anything else at the end

of the presentation, Mr. Bezos piped up: "Yeah, can I have your

notes?" Mr. Wilke recalls.

PowerPoint presentations are now banned at Amazon, and it's

common for meetings to begin with a long stretch of quiet as

everyone reads six-pagers -- a tactic Mr. Bezos adopted to ensure

that executives actually process the proposal before discussing

their merits and asking questions.

"One of the things I flagrantly ripped off from Amazon was the

narrative, " said Adam Selipsky, the CEO of software maker Tableau.

He worked for 11 years for Amazon's cloud-computing arm, Amazon Web

Services, and was a member of the inner circle of senior executives

called the "S-team" before leaving for Tableau. He said people

found the six-pagers weird at first, but that it's caught on.

"There's a lot more democratic participation in the discussion

by using the narrative," he said.

Amazon introduced its leadership principles in 2002 after

noticing there were a number of different words and phrases that

kept coming up when discussing leadership, said Mr. Wilke. He and a

small group of colleagues took a shot at writing their first set of

principles and presented them to Mr. Bezos, who said they weren't

"Amazonian enough." They revised the list and today it is used in

hiring, employee reviews and business decisions.

At Amazon, candidates who pass a phone interview then meet in

person for up to six back-to-back meetings with different employees

one-on-one. Each employee is digging for examples for how the

candidate's experience relates to a specific leadership principle

or competency of the job. One of the interviewers is a so-called

bar raiser unaffiliated with the role the person is interviewing

for, and is specifically trying to glean whether the person

embodies the leadership principles.

Laura Orvidas says she is incorporating some of Amazon's hiring

techniques at onXmaps Inc., a digital mapping company for hunters

and outdoorsmen, where she became CEO in 2018 after nearly 18 years

at Amazon.

She said Amazon's leadership principles became so ingrained that

she would find herself using them with her kids without thinking,

saying things like: "Honey, really good bias for action there."

According to that principle, leaders remember that speed matters

and that many decisions and actions can be reversed and don't need

extensive study.

At Amazon, she ran the multibillion-dollar consumer electronics

segment, which she said gave her necessary experience for running a

company. That's a quality that draws executive recruiters to

Amazon's ranks: Its sprawling empire -- with businesses as diverse

as advertising, prescription-drug delivery and a movie studio --

means that division heads have their own fiefs that can be bigger

than the publicly traded companies they compete against.

Recruiters also say that clients want CEOs with technological

expertise, data-driven approaches and an ability to deal with

disruption or be a disrupter. With Amazon, "a lot of clients want

to know what's the secret sauce," said Lorraine Hack, a senior

client partner for Korn Ferry's technology recruiting practice.

"The whole culture is so entrepreneurial, efficient,

get-things-done," she said. "That's a CEO personality."

Like GE in its heyday, Amazon is viewed as a so-called "academy

company" where leaders are groomed, said Ms. Hack, adding that

PepsiCo Inc. is considered one as well.

Some Amazon executives go elsewhere because they perceive a

ceiling at the upper end of its ranks, says Nada Usina, co-leader

of executive recruiting firm Russell Reynolds Associates' global

technology practice. That's because Amazon's top leaders tend to be

long tenured. Mr. Wilke, 52, just hit his 20th anniversary. Amazon

Web Services chief Andy Jassy has been at Amazon for more than 22

years. The S-team, with 18 high-ranking executives, rarely has

openings.

Mr. Wilke said he hopes that many leaders want to stay at

Amazon, but "I am also proud that they're going out into the world

and building great things."

Among those who ran into difficulty after they left, Tim Stone

lasted eight months as chief financial officer of Snapchat parent

Snap Inc. after two decades at Amazon. Mr. Stone wasn't a good

cultural fit for Snap, said people familiar with events. The issues

came to a head when he went directly to Snap's board of directors,

and over CEO Evan Spiegel's head, to ask for a big raise, the

people said. He is now CFO of Ford Motor Co.

Mr. Stone didn't respond to requests for comment.

When Dan Lewis began developing the business model for Convoy, a

digital freight network valued at $2.75 billion, he sketched out a

circular diagram, outlining how its business goals (better cost

structure) would tie into customer benefits (lower rates to

shippers), on the back of a piece of scrap paper at a Seattle

coffee shop.

Amazon lore is that Mr. Bezos also used a napkin to sketch out

Amazon's similar "flywheel" business model. The cycle by which

Amazon increases selection, which lowers costs and prices and gives

customers reason to keep shopping, is something still inculcated in

the workforce 25 years later.

Convoy's flywheel, which revolves around getting shipment

volumes for truck drivers to better utilize empty space in vehicles

and drive down costs, is laminated in each conference room of the

company, he said. The company's leadership principles are on the

other side of the flywheel. Mr. Lewis was general manager of new

shopping experiences at Amazon until 2015, when he started Convoy,

which counts Mr. Wilke and Mr. Bezos as personal investors.

Cate Khan, co-founder of shopping website Verishop and a 7-year

veteran of Amazon, said the first thing she did when she was

thinking about the company's positioning was write a fictional

press release -- what Amazon refers to as a "PRFAQ." Her co-founder

and husband, Imran Khan, who was Snapchat's chief strategy officer,

has absorbed some of the lessons himself: In the early stages of

Verishop, he requested six-pagers from various teams.

Ms. Khan took something else from Amazon with her. In September,

Verishop announced free one-day shipping.

Write to Dana Mattioli at dana.mattioli@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 21, 2019 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

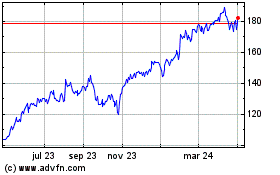

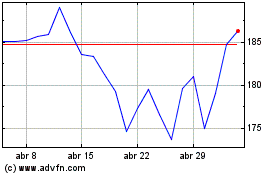

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024