By Nour Malas and Rob Copeland

SAN JOSE, Calif. -- Technology giants helped pump the West Coast

full of choking traffic and expensive homes. Now they are trying to

fix the damage.

The challenge, and all its many complications, is playing out in

real time in this city.

Google wants to build a campus of more than 6 million square

feet here, with twice as much office space as the Empire State

Building. The plans include a revamped downtown area around an old

train station with thousands of apartments, shops and community

spaces. The pitch would essentially remodel San Jose as a

21st-century company town, where a dominant employer lifts the

local economy for decades to come.

Some residents welcome the potential lift. Others fear the

worst, having seen nearby towns struggle to recruit firefighters

and teachers because few can afford to live near their jobs.

Activists protesting gentrification have objected to the secrecy

around initial talks and booed the city mayor at public events. At

one city council meeting in 2018, activists chained themselves to

chairs to protest the project. Police used bolt cutters to remove

them.

The Alphabet Inc. unit is negotiating with San Jose officials

after three years of preliminary discussions. Local community

groups want a quarter of the housing in the development to be sold

at below-market rate. They're also drawing a line at private Google

buses, citing inequality and environmental concerns.

Google has said it would build some below-market housing units

but hasn't determined the exact figure. It won't commit to nixing

the buses.

The back and forth is a microcosm of a battle that has played

out over and over across the region. Technology has brought

extraordinary wealth to Silicon Valley. It has also worsened the

area's housing shortage and a widening economic divide. The

question facing San Jose, the nation's 10th most populous city, is

whether it can bring in a major employer while managing the

downsides.

Elizabeth Valdivia, a 60-year-old security worker, could no

longer afford to live in her hometown of Mountain View after Google

built out its global headquarters there. She rents a room in an old

San Jose apartment building for her disabled brother while she

lives out of a rusted 1997 Mercury Tracer sedan.

"Where will we go?" she says. "You can't have 20,000 Googlers

come here and not have mass displacement."

In private meetings, local officials say, Google representatives

have said the company's primary responsibility is to shareholders,

not to solving the ills of an entire region. Google has offered

smaller concessions, such as curbing perks like free snacks for

employees to encourage them to spend money outside the office and

build up a broader neighborhood.

"We're trying to create the best version of all the voices we

have heard, " says Google real-estate development director Alexa

Arena. She says that from the start, Google decided not to seek tax

breaks or run a competitive bidding process between cities --

strategies that fomented a public outcry during Amazon.com Inc.'s

highly-publicized second-headquarters hunt.

"HQ2 is the opposite of what we are trying to do," says Ricardo

Benividez, a Google director charged with incorporating San Jose

public opinion.

San Jose's mayor, Sam Liccardo, said the city was working hard

to get it right: "It's high stakes, and it's a great opportunity."

Mr. Liccardo called the Google project an opportunity to reinvent

Silicon Valley away from a model where "you create a moat, put

alligators in there, and surround it with a sea of parking."

Tech companies, which largely blame the housing shortage on

local regulations that restrict home building, are starting to

respond. Last year Google pledged $1 billion, mostly in land

donations across the San Francisco Bay Area, to address the issue.

In November, Apple Inc. said it would commit $2.5 billion to go

toward affordable housing in California, including to help the

state develop and build low- to moderate-income housing and to help

first-time home buyers with financing.

Two years ago, the company took heat from neighboring towns for

spending $5 billion on a new headquarters that included roughly

10,000 new parking spaces but no additional housing.

Facebook Inc. was the first big Silicon Valley firm to start its

own fund for affordable housing in 2016 as it negotiated with the

city of Menlo Park over its expansion. In a pilot program for

teachers who want to live in Palo Alto, the company covers any rent

above 30% of their income. Last year the subsidy was an average

$31,582 per teacher.

Facebook has also become a political force in Sacramento,

putting hundreds of millions of dollars behind housing bills and

supporting a grass-roots movement of housing advocates in

California.

"We can fund all the housing we want, but that doesn't actually

get it built," says Facebook's Menka Sethi, who leads the company's

housing efforts. "Government needs to approve more."

Missing out

San Jose has long been the stepchild of Silicon Valley.

Its first city planner in the 1950s envisioned it as a Los

Angeles of the north, a collection of single-family homes scattered

across cherry, apple and plum orchards. The city designated

relatively little land for commercial use, and mostly missed out as

Palo Alto, Cupertino and other towns around Stanford University to

the northwest became startup central.

Over the past eight years, Silicon Valley added jobs at six

times the rate it added housing, according to local transport and

housing agencies. San Jose, however, gained more residents working

in cities to the west and north than it did new jobs, depriving it

of business taxes and the daytime dollars its residents were

spending everywhere else.

The city's streets are all but abandoned during the day. The

population swells past 1 million only after dark, when commuters

trickle home. The soundtrack is the roar of jet engines from the

airport downtown.

San Jose has a reputation as a pocket of affordability in

Silicon Valley, in a state that boasts 91 of the 100 most expensive

ZIP Codes in the country, according to real-estate data firm

PropertyShark.

Google, where the median employee pay is almost $250,000 a year,

almost triple San Jose's median household income, has the potential

to reverse those trends.

City officials say they started talking to Google in 2016. Kim

Walesh, San Jose's economic development director, says her team was

gauging if Google would consider expanding in San Jose, arguing

that a large number of the search giant's employees already lived

there.

"Quite honestly," she says, "there was no interest."

In late 2016, Mark Golan, Google's real-estate head, called the

mayor, Mr. Liccardo, and said Google was in. It would develop a

complex surrounding downtown San Jose's dilapidated Diridon train

station with as many employees as Google's headquarters a few miles

to the north. The development could be ready as soon as 2024.

The city also has plans, yet unfunded and decades away at best,

to transform the station into a hub for light rail, metro and

bullet train systems connecting the city to Silicon Valley's

smaller towns, as well as to San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Google's Mr. Golan told officials his company would buy land

parcels downtown through a real-estate broker, to keep the

company's name out of the press.

Mr. Liccardo agreed to swear to secrecy while negotiations

continued. The mayor, along with two dozen city staffers including

council members and their aides, signed nondisclosure agreements

starting in February 2017.

The agreements became public that June. Two weeks later, the

city council voted to start exclusive negotiations with Google to

sell the land. No other bids were solicited. Google has spent

around $450 million so far buying public and private property for

the expansion.

"It felt like, 'This is happening,' as opposed to, "Do we want

Google in our community, and is that the best thing for us?' " says

Liz Gonzalez, a local activist.

Mr. Liccardo says the NDAs were appropriate to stem real-estate

speculators, and because the city didn't make any decisions related

to public benefits during that time. Google executives now say that

they were a mistake from a public-relations standpoint, and that no

further NDAs are planned.

Already the largest lobbying spender among major technology

companies in Washington, D.C., Google has recently become a major

philanthropic force in San Jose.

In early 2018 San Jose assembled a Station Area Advisory Group

of various community groups. Several groups on the board receive

money from the search giant, and Google has bumped up its donations

in the past two years, according to public disclosures and

interviews.

Google's Ms. Arena says there's no quid pro quo. "It's a little

bit of a double-edged sword," she says of donations to community

groups with a say in the outcome. "We absolutely need to support

the organizations who are helping to think through massive regional

programs."

A walk-through of the site last year revealed actual

tumbleweeds. Parking lots were mostly empty. Google's Mr.

Benividez, playing the role of tour guide, was delighted to find a

full bike-sharing dock, but it wouldn't accept his credit card when

he tried to rent one.

Several homeless residents were sleeping in makeshift camps.

Google gave $1 million to a local nonprofit that runs shelters in

November.

The tour continued past a reedy, unkempt creek. Ms. Arena said

Google is negotiating with environmental groups about what, if

anything, it can to do improve the waterfront, given local

regulations.

San Jose council member Johnny Khamis said the variety of

demands levied on Google risked scaring the company.

"If we keep forcing them to pay for housing and parks, they will

go to Houston or Austin," he said. He balked at the idea that

companies like Google should be involved in building housing: "They

will end up fixing toilets rather than fixing code."

The Station Area Advisory Group meetings have been dominated by

talk of housing.

A recent hearing in a windowless conference room at San Jose

City Hall demonstrated the mix of viewpoints that all involved must

navigate in a city as large and diverse as San Jose. Google's Mr.

Benividez sat quietly to the side as a dozen speakers railed

against his employer.

The first speaker during the public comment period, local

resident Paul Soto, began reading excerpts from Aldous Huxley's

dystopian novel "Brave New World" with dramatic verve.

"Democracy can hardly be expected to flourish," Mr. Soto said,

"in societies where political and economic power is being

progressively concentrated and centralized."

Another resident compared Google to "colonizers who set sail for

San Jose." She broke into tears after her two minutes at the

microphone were up.

City officials have banned the use of the word "campus" in

internal and external communications about the Google project,

fearing it triggers a negative association with the sprawling,

insular workplaces of other tech giants.

Plans for the new development released in October included up to

5,000 units of housing. That would accommodate roughly one-fifth of

Google's employees at the site.

As part of its effort to win over locals, it spent $40,000

restoring a San Jose icon, a neon sign of a plump yellow pig once

used for an old meat factory. It marked the event with a party in a

parking lot in June that was covered closely in the local

media.

On Montgomery Street in downtown, two blocks from where Google's

new village may rise, shopkeepers and homeowners are awaiting a tap

on the shoulder to sell to the company.

A row of stores -- a cement showroom, a welding shop, a food

wholesaler -- and a shingle-roof home have already sold to Google.

Across the street, mechanic George Lopez hoped his turn would come

next: "It will be a beautiful thing. Jobs. Tourists. More people

spending money."

Ms. Valdivia, who has taken on more hours at work to save for an

anticipated rise in her brother's rent, sees it differently. "We're

going to be driven out of town."

Write to Nour Malas at nour.malas@wsj.com and Rob Copeland at

rob.copeland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 28, 2020 13:19 ET (18:19 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

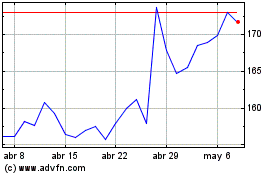

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024