By David Gauthier-Villars

ISTANBUL -- Turkey's parliament has approved new laws on social

media that give the government more power to police content on

Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and other networks, sending a chill

through the country's human-rights activists.

Backed by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling Justice and

Development Party, the legislation provides authorities with

significant ammunition against their critics. Under the new

measures, social media companies will be required to have a

permanent representative in Turkey, take steps to store Turkish

users' data in the country, and execute court orders to take down

content.

Failure to comply will expose operators to a five-step regime of

sanctions ranging from fines to being stripped of advertising

revenue and being subjected to near-complete access restrictions.

It isn't yet clear when the new measures take effect.

The scope of the legislation, passed Wednesday after a marathon

16-hour session, has alarmed opposition leaders and free-speech

advocates. They say social media has become one of the last few

spaces to express dissent after tycoons loyal to Mr. Erdogan

acquired television channels and national newspapers following a

failed coup attempt in 2016. Dozens of other outlets were closed

amid accusations they supported the plotters.

As critical voices migrated to social media, building a

significant audience, especially among youth, the government also

cracked down on dissent over the internet and social networks.

"Social media is a lifeline for many people who use it to access

news, so this law signals a new dark era of online censorship," Tom

Porteous, a director with Human Rights Watch, said.

The law was adopted less than a month after Mr. Erdogan

complained that some people had posted insults under a social media

announcement of the birth of his eighth grandchild, and vowed more

government powers to regulate the internet.

"Do you understand what it means, why we are against YouTube,

Twitter, Netflix and all those social media sites," Mr. Erdogan

said in a speech on July 1. "Turkey is not a banana republic. We

will spurn those who spurn the administrative and judicial

institutions of this country."

Twitter Inc.'s reaction will be closely watched. The platform

recently clashed with the Turkish government, saying in June that

it had permanently deleted more than 7,000 "fake and compromised"

accounts it alleged had been used as part of a

centrally-coordinated effort to "amplify political narratives

favorable to the AKP."

The Turkish presidency, which makes extensive use of Twitter to

release announcements, said the allegations were untrue. "This

arbitrary act, hidden behind the smokescreen of transparency and

freedom of expression, has demonstrated yet again that Twitter is

no mere social media company, but a propaganda machine with certain

political and ideological inclinations," Presidency Communications

Director Fahrettin Altun said in a statement.

A spokeswoman for Twitter said the company had no immediate

comment on the new law. Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Google,

which operates the YouTube broadcast service, didn't immediately

respond to messages seeking comment.

Over 400,000 internet sites are blocked in Turkey, including

many news portals, and thousands of people are being prosecuted

over their social media posts, according to Yaman Akdeniz, a

professor at the Bilgi University and an internet rights expert.

According to data he has compiled, more than 90,000 investigations

and nearly 20,000 prosecutions have been launched in recent years

over alleged insults against Mr. Erdogan in his capacity as

president.

"There was already extensive internet censorship in Turkey, even

before we began talking about the new law," Mr. Akdeniz said. "So

the situation was already bad and we're moving from bad to

worse."

Adoption of the new law coincides with a drop in support for the

AKP, as Mr. Erdogan's ruling party is known in Turkish. Recent

surveys suggest it would garner about 30% of the votes if

legislative elections were called early, compared with 43% in the

July 2018 vote. Pollsters have said the surveys also point to a

growing disconnect between the party and the aspirations of younger

Turks.

Opposition politicians condemned the new measures, saying it

would limit freedom of expression. "You can't use social networks

when it serves you and appeal to prohibition when you receive

dislikes," Engin Ozkoc, a lawmaker with the Republican People's

Party, said during parliamentary debates.

Atilla Yesilada, an economist who no longer appears on

mainstream media in Turkey but broadcasts his critical views of the

government on a YouTube channel, a Twitter account and a website,

said the new attempt to control speech in the internet space would

fail.

"It is going to backfire," said Mr. Yesilada, an emerging market

consultant for GlobalSource Partners, a research and analysis

group. "People like social media and think it's the most-trusted

news source. If you try to shut it down, there will be a protest

vote."

Write to David Gauthier-Villars at

David.Gauthier-Villars@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 29, 2020 11:01 ET (15:01 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

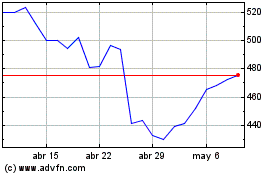

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024