By Richard Rubin

Konstantin Anikeev, an experimental physicist, assembled

everything he needed for an inquiry far outside his field.

His materials included American Express cards, the government's

view that credit-card rewards aren't income, and his own

willingness to spend time buying gift cards and money orders. He

pulled the concept from personal-finance websites: Exploit the

difference between unlimited 5% rewards and lower fees on gift

cards and money orders.

"If one has a theory, one can test it experimentally. Some are

easier to test," Mr. Anikeev said. "Others require a Large Hadron

Collider or something like that. But this one was a bit more

accessible."

It (mostly) worked.

Mr. Anikeev's financial-optimization plan in 2013 and 2014 --

including $6.4 million in credit-card charges -- led to an Internal

Revenue Service audit and a finding that he and his wife had more

than $310,000 in income that should have been taxed.

Judge Robert Goeke's decision last month largely affirmed

longstanding Internal Revenue Service practice, which says

credit-card rewards are usually nontaxable rebates. In other words,

buying a pair of shoes for $100 and getting a 5% reward is really a

$95 purchase, not $5 of income. But the judge also offered the IRS

avenues for tougher enforcement.

Mr. Anikeev's interest in personal finance started when he was a

graduate student with plenty of time but little money. The

Connecticut resident drew on ideas from personal-finance websites,

he testified at his 2019 trial.

In 2009, he, like many others, used a rewards credit card to buy

$1 coins from the U.S. Mint, profiting from the lack of shipping

charges on them.

By 2013, he found the strategy that would land him in tax

court.

His American Express card offered unlimited 5% rewards at

grocery stores and pharmacies after he had spent $6,500. So Mr.

Anikeev used his AmEx card to buy prepaid Visa gift cards at

grocery stores, routinely stopping during his commute and

purchasing the maximum allowed per day at a store. He often used

the gift cards to buy money orders, then used the money orders to

make deposits in his bank account, then used that money to pay his

credit-card bill.

In a $500 transaction, the 5% rewards would yield $25 -- more

than enough to cover gift-card fees of about $5 and the $1 fee on

the money order.

The millions of dollars of those transactions tripped the

sensors at the Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement

Network, which investigates money laundering, an IRS lawyer said

during the trial. That agency kicked the case to the IRS, which

said he owed back taxes. Mr. Anikeev took the government to court,

bringing a tub of gift cards to his trial to demonstrate what he

did.

"They sort of picked the fight with the wrong person," said his

lawyer, Jeffrey Sklarz. "They should have picked someone who was a

hot mess."

Judge Goeke issued a split ruling. Rewards earned on purchases

of Visa gift cards aren't taxable, he ruled, because the cards are

products; most but not all of Mr. Anikeev's transactions happened

that way. Rewards earned on purchases of money orders or reloading

debit cards are taxable, the judge determined. The IRS already says

rewards can be taxable if they are earned without spending, such as

a bonus for opening a bank account.

The two sides still must calculate what additional taxes Mr.

Anikeev might owe. Andrew Johnson, an American Express spokesman,

declined to comment on Mr. Anikeev's case. He said the company uses

a "combination of strategies" to police the rules of rewards

programs that don't allow purchases of cash equivalents. The IRS

doesn't comment on active litigation.

Mr. Anikeev said he was somewhat disappointed. He said the

judge's distinctions ignore that the IRS classifies money-order

businesses as services and that money orders are items, and thus

any rewards from purchasing them shouldn't be taxable.

Judge Goeke raised an alternate way for the IRS to attack future

transactions like Mr. Anikeev's.

Perhaps, he wrote, if gift cards are property, the rewards

reduce a person's cost basis in that property. Following that

logic, exchanging gift cards for money orders would be selling

property for a gain. The judge urged the IRS to consider

regulations or public statements to offer clearer rules in case

people are confused.

"How do you know when you cross the line?" said Robert Tobey, a

partner at the Grassi accounting firm in New York.

The case highlights a flaw in the IRS approach to credit-card

rewards, said Stephanie Hoffer, a tax-law professor at the McKinney

School of Law at Indiana University.

Treating them like rebates makes sense for purchases of

products, she said. But in Mr. Anikeev's case, there is no purchase

of goods or services, just a circular money flow.

"I was really shocked by the outcome of the case. To me, this

seems clearly to be income," Ms. Hoffer said. "At the end of the

day, does this taxpayer have an accession to wealth? The answer is

clearly yes."

Ordinary credit-card rewards users need not fear that they are

earning taxable income. Even so, the case is a warning that

activity far outside the norm might catch the government's eye, Mr.

Tobey said.

Mr. Anikeev said he isn't doing anything like what he did in

2013 and 2014, though he is still just as interested in personal

finance.

"He's a very mathematical, brilliant person," said his lawyer,

Mr. Sklarz. "And this was just something he thought was fun."

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 07, 2021 09:14 ET (14:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

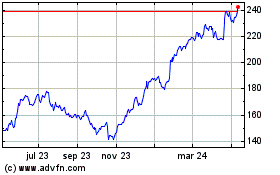

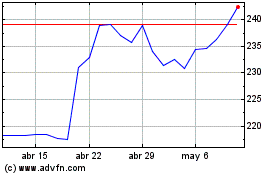

American Express (NYSE:AXP)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

American Express (NYSE:AXP)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024