By Jared S. Hopkins

A half-century ago, freshman Barney Graham rolled onto the Rice

University campus in a new 1971 Ford Mustang. To blow off steam

that year, he launched water balloons off the dorm roof with his

new roommate Bill Gruber, who drove a hand-me-down Dodge

Monaco.

Barney, a top high-school athlete and valedictorian from a

family farm in Kansas, starred in intramural sports at Rice. Bill,

a high-school academic star from a Houston suburb, said Barney made

up for his own athletic deficiencies when they played football and

softball.

Barney recalled thinking when they met that Bill probably "knew

a lot more than I did, and I was going to have to work hard to

catch up." He turned to Bill for help keeping pace with math and

science courses, while at the same time trying to outdo his

roommate. "We were very competitive, but I think in a good way,"

Bill said, "We wanted to be the best, frankly, at knowing

everything related to science."

Last year, the two men returned to competition, this time in a

race to stop the pandemic.

When Moderna Inc. announced in November that its vaccine had

proved highly effective against Covid-19, Dr. Barney Graham, a

government scientist who helped design the shot, emailed his old

pal. Dr. Bill Gruber ran the clinical trials of the vaccine from

Pfizer Inc., which had announced its own similarly impressive

results a week earlier.

"I'm glad we were able to keep up with you," Dr. Graham, a

laconic 67-year-old, wrote the fast-talking Dr. Gruber, 68.

The two men recalled their time together as 18-year-old

freshmen, spanning various areas of competition, grades, and

collaboration, studies and mischief.

One of their first trial-and-error experiments came from trying

to wring more space from their cramped dorm room. Their idea: drill

holes in the concrete ceiling and hang their beds up high with

metal chains. "I had just come from a farm, and I thought I could

rig up just about anything, " Dr. Graham said.

They hoisted the beds on the chains and slept soundly for weeks.

One night, Dr. Gruber's bed came untethered, sending him crashing

into his desk below. The roommates made some design tweaks, and the

beds remained suspended through graduation four years later.

The two men lost track of one another after leaving Rice for

medical school, Dr. Graham at the University of Kansas, Dr. Gruber

at Baylor College of Medicine.

At a 1986 medical conference in New Orleans, Dr. Gruber, then a

pediatrician at Baylor, was setting up a display of research

findings for an illness called respiratory syncytial virus, known

as RSV, that can kill infants and the elderly. He was shocked to

see his former roommate standing next to him, showing his own

research on the same virus.

"It was a pretty remarkable coincidence," said Dr. Graham, who

was an assistant professor at Vanderbilt's vaccine research center

at the time. The two men caught up, and Dr. Gruber soon joined Dr.

Graham at Vanderbilt.

They remained in Nashville through the 1990s and occasionally

co-wrote papers on virus research, a field they had found

independently.

"We're almost like the double helix," Dr. Gruber said, not

surprisingly using a DNA analogy. "We spread apart and come back

together, spread apart and come back together."

In 1999, Dr. Gruber left for to pursue vaccine development at

drugmaker Wyeth (later acquired by Pfizer). A year later, Dr.

Graham joined a new vaccine research center at the National

Institutes of Health. Again, years passed with little contact.

Dr. Graham's lab made a breakthrough in 2013 regarding the

structure of an important protein in the RSV virus, a finding that

laid the groundwork to understanding the spike protein in the new

coronavirus.

He couldn't present his findings at a planned medical conference

because of a two-week government shutdown that kept federal

employees from traveling. He and his wife instead used the time for

a road trip that took them close to Dr. Gruber's house in upstate

New York. Dr. Graham left a voice mail. Dr. Gruber called back and

invited the couple to his house for dinner.

Sitting at the kitchen table, Dr. Gruber said he heard about his

former roommate's breakthrough research. Dr. Graham opened his

laptop and flipped through the PowerPoint slides on the RSV virus

he had prepared for the conference. "I can kind of hear the echo of

my wife saying, 'Why are we talking about this during dinner?' " he

recalled.

Dr. Gruber sent a team from Pfizer to visit Dr. Graham's

government lab in Maryland to discuss the research. Pfizer relied

on the lab's advances to develop its own RSV vaccine, which is now

in human testing.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought the two men together one more

time.

Dr. Graham's lab joined with Moderna to design a vaccine using a

new and unproven gene-based technology called mRNA. The day after

the Moderna vaccine began human trials in March, Pfizer announced

its own vaccine partnership with BioNTech SE, also using mRNA.

They spoke by phone a few times each month, discussing the

biology of the virus and its impact on their lives. They exchanged

emails and texts as the global death toll rose into the hundreds of

thousands.

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines started late-stage, or Phase 3,

trials the same day in July. In early November, Pfizer announced

its positive results, and a month later was cleared for use by the

Food and Drug Administration. Moderna's authorization followed by a

week.

"The fact is that we both want everybody to win here," said Dr.

Graham, deputy director of the National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases Vaccine Research Center.

Looking back, Dr. Graham said, he and Dr. Gruber "marvel at how

over 50 years this all transpired."

When the topic of their competitive spirit came up during a Rice

alumni panel last year, Dr. Gruber joked how Dr. Graham had

reminded him how Pfizer's trial started several hours behind

Moderna's.

Dr. Gruber also offered this advice to the students listening

in.

"Get along with your fellow roommates," he said, "you just never

know where that path is going to lead."

Write to Jared S. Hopkins at jared.hopkins@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 25, 2021 11:37 ET (15:37 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

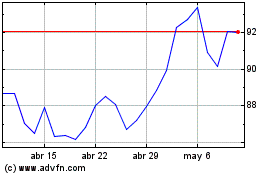

BioNTech (NASDAQ:BNTX)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

BioNTech (NASDAQ:BNTX)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024