By Thomas Gryta

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (February 14, 2019).

The turnaround of General Electric Co. depends on the revival of

its core power business, a reversal that will require Chief

Executive Larry Culp to churn through a $92 billion sales backlog

marred by lousy projects.

"We certainly have some business that we need to work through

where the margins and the cash generation isn't great," Mr. Culp

said in a recent interview. The new GE boss called it an

"inheritance tax."

Boston-based GE lost $200 billion in market value in 2017 and

2018 as it struggled to cut costs and misjudged market shifts. The

backlog of orders in the power division -- won in recent years both

by GE salespeople and companies GE acquired -- wasn't always built

on attractive terms, as previous leaders chased market share.

"There was a level of confidence that if we got the order it

would be a good thing for GE and the GE shareholder," he said. But

that didn't turn out to be true. The company recorded $750 million

in charges from the power business in the fourth quarter to reflect

adjustments to those realities.

Mr. Culp said some of the projects accompanying GE's takeover of

the power business of French rival Alstom SA in 2015 "came in at

low margins." GE set aside cash reserves on some of those projects

in previous quarters to cover expected shortfalls.

"In others, we've learned a few things of late," he said.

The power business, which makes and services turbines that

convert fuel into electricity, is GE's oldest business and, until

recently, was also its largest. The division has been hit by

mismanagement, bad deal making and a market shift away from fossil

fuels in favor of renewable sources for a greater portion of

electricity generation. GE has a separate renewables division that

sells turbines to wind farms and hydropower plants.

Mr. Culp has spent much of his time since taking over in October

focused on the power business. He wants to ensure salespeople don't

easily agree to lower prices to lock up a sale.

"We've changed the compensation scheme where we are paying the

sales leaders no longer on volume but on margins," he said, adding

that there are early signs the shift is working. "That isn't

something we are going to fix in a quarter or two."

As of the end of 2018, GE had a companywide backlog of $391

billion, a figure that represents a near doubling in just seven

years and includes hundreds of orders for jet engines. The power

business had $92 billion of those orders and reported a loss of

$872 million in the fourth quarter.

The power backlog is large, but there is little information on

what it contains partly because the details of commercial

agreements with customers are kept private. The backlog includes

both equipment orders and service contracts, some of which cover

more than a decade. Once the machines are delivered or work is

performed, GE books the backlog as revenue.

GE made its biggest ever industrial deal when it bought Alstom's

power business, but the deal was soured by delays, regulatory

compromises and the state of Alstom's assets. Last year, GE took a

$22 billion charge to write down the value of the business.

The deal, while enlarging the power business, also gave GE the

ability to construct power plants, rather than just supply their

equipment. Analysts and investors say that construction business

has proved to be more challenging than equipment manufacture

because of its complexity, cost overruns and long timelines.

When the power market hit one of the biggest downturns in years,

GE Power was sitting on too much unsold inventory. Rather than use

its size to raise prices, the division had pushed for market share,

undercutting rivals such as Siemens AG to win sales.

"That is the nature of this business," Barclays analyst Julian

Mitchell said. "You've got big projects, and you've got big risk to

manage."

GE also used aggressive accounting to dress up the business. It

sold equipment upgrades to some customers by rolling them into

existing service contracts. It also changed its profit assumptions

for such agreements to record gains. The accounting of these

service agreements is under investigation by both the Securities

and Exchange Commission and the Justice Department.

GE says it has reviewed the backlog, including more than 1,000

service and equipment contracts, to gauge cost and other risks. Mr.

Mitchell expects the company will continually review the portfolio

of future work and sees such scrutiny as "more likely to yield bad

news than good news."

Mr. Mitchell expects it will take two to three years for GE to

work through the backlog. He doesn't project the power division to

be profitable again until 2021.

Investors are watching the power business closely. This month,

Fitch Ratings shifted to a negative outlook for its credit rating

on GE citing power's poor outlook and a need to cut costs, improve

project completion and address quality issues.

Fitch expects GE's cash flow to be well below other industrial

companies for the next two to three years as the restructuring

takes effect.

It will take some time, Mr. Culp said, for all the

less-attractive deals to work their way out of the system. "The

real challenge for us," he said "is to make sure we aren't

repeating any of those mistakes."

Write to Thomas Gryta at thomas.gryta@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 14, 2019 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

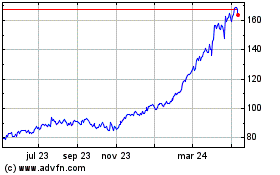

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2024 a May 2024

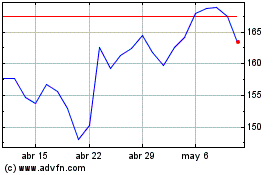

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De May 2023 a May 2024