By Sharon Terlep

Almost every day an employee at Procter & Gamble Co.'s plant

in Albany, Ga., a town with one of the nation's highest rates of

coronavirus, learns that someone close has become seriously ill or

died of Covid-19.

There is little time for consolation between co-workers. They

are all racing to churn out one of the most in-demand products in

America: toilet paper.

"It's a lot quieter here than it used to be," said John

Patterson, a 16-year veteran of the plant, which makes Charmin

toilet paper alongside Bounty paper towels. Workers, who must stay

6 feet apart, console one another over headsets and on video

calls.

P&G, which produces household staples from Tide detergent to

Pampers diapers, is the biggest U.S. maker of toilet paper with

close to 30% of the market. The sprawling Albany factory, one of

six that make toilet paper, is P&G's second-largest U.S. plant.

It makes products that generate roughly $1.3 billion in annual

sales, according to the Georgia Manufacturing Alliance.

The factory has ramped up production by 20% of both toilet paper

and paper towels, even as it revamps its operations to keep its

roughly 600 workers healthy. Among other measures, it has

instituted pre-shift temperature checks and staggered start times.

P&G declined to comment on whether employees have tested

positive.

The plant sits in a midsize town of 75,000 people ravaged by the

new coronavirus. More than 1,020 people have tested positive in

Dougherty County, which includes Albany, and 62 have died as of

Thursday afternoon. More people have died in the county than in

Fulton County, which includes Atlanta and has a population more

than 10 times larger.

Health officials trace the spread of coronavirus in Albany to a

late-February funeral that drew more than 100 mourners, including a

man who later died of Covid-19.

In mid-March, Albany Mayor Bo Dorough received word from county

health officials that a few residents had tested positive for

coronavirus. Officials thought the cases were isolated instances.

"We thought it was an anomaly," Mr. Dorough said. "But after those

three deaths, things just started to cascade downward and it hasn't

stopped since."

The community and the factory have been through rough stretches.

Albany has among the state's highest rates of crime and poverty. In

2018, a hurricane wiped out power for days to thousands in the

community. A year before that, a tornado leveled the warehouse at

the P&G complex.

Around the same time Mr. Dorough was learning of the first

deaths in his town, executives at P&G's Cincinnati headquarters

were strategizing about how to ramp up production. The company had

already mobilized safety plans in the U.S. that it had previously

put in place in China, the company's second-largest market.

"I started to realize, this isn't going to skip over us," said

Rick McLeod, who oversees product supply for P&G's family care

unit, which includes toilet paper. "There were cues that this is

going to be a big deal. Then the floodgates opened and everyone

realized the seriousness."

The state of Georgia and the U.S. Department of Homeland

Security consider the plant an essential business, so it has

remained open as offices, shops and restaurants close throughout

the rest of the state.

Demand for toilet paper shot up in the outbreak's initial weeks,

doubling in the second week of March, according to Nielsen. Before

the surge, Americans spent roughly $9 billion a year on toilet

paper. The internet flooded with memes and jokes about

toilet-tissue scarcity, as well as tales of serious panic. P&G

added a prerecorded message to Charmin's toll-free line

specifically for people hunting for toilet paper.

While Americans aren't using more toilet paper amid the

pandemic, they are going through substantially more at home. The

thin, scratchy tissue found in office bathrooms and public

restrooms is different enough that it is generally built at

separate plants -- with different supply chains -- and can't be

redirected to store shelves overnight, said analyst Jonathan Rager

of Fastmarkets RISI, an analytics firm specialized in the pulp and

paper industry.

Making toilet paper in bulk requires a massive machine, a

four-story-tall collection of intricately pieced-together parts,

which costs billions of dollars and takes months to build.

Bathroom tissue begins with wood chips that are turned into

pulp. The machinery cleans the pulp and feeds it through massive

rollers that soak out any water. The pulp is then chemically

whitened and then spread on a screen and put through a hot dryer,

emerging as a delicate sheet of paper that gets rotated into a

spool. A single spool can hold close to 50 miles of paper, which is

then embossed both for aesthetics and to thicken the sheets.

A separate machine constructs cardboard into tubes roughly

five-feet long. Two sheets of the finished paper are combined to

make two-ply tissue, which is then wrapped around the cardboard

tubes. A machine seals the roll with a light glue and then a

circular saw cuts the long roll into bathroom-sized rolls that are

packaged and loaded for delivery.

A big toilet paper operation could churn out a few million

individual paper rolls a day, with that number varying

significantly based on how many lines the factory devotes to toilet

paper and the type and size of each roll, said Mr. Rager of

Fastmarkets.

Quickly changing over a line or adding production at another

factory wasn't an option for P&G. But in Albany, P&G had an

idled piece of equipment that, if put to use, could increase

volume.

Setting up the equipment to help make the current product, and

staffing it with workers trained to use it, would typically take

months for Albany's team of 10 technicians. So P&G sent a

half-dozen engineers from other plants to help. The equipment was

operational within two weeks, but the company had another problem.

The engineers' return flights had been canceled as airlines shut

down amid the virus's spread.

P&G CEO David Taylor, whose early career included a

three-year stint in the 1980s as an operations manager of the

Albany factory, directed a corporate jet to be sent to Georgia to

retrieve the workers and take them home to Missouri and

Pennsylvania.

Mr. McLeod, the P&G executive, also started his career at

the Albany plant and lived there nearly a decade. His voice cracked

as he talked about a retired technician, in her late 60s, whom he

supervised in his early days who died of Covid-19, along with her

daughter, who was in her early 40s. Earlier that day, he learned

that an Albany employee lost their father.

"The more we can serve our consumers the better it is for

everyone," he said. "If they can just see some product in the

store, it will help. There's a sense of pride of being able to

deliver that thing that's so needed right now."

Increasing production while keeping workers safe is a challenge

for many U.S. employers, from meatpackers to factories making

hospital ventilators. P&G has started producing face masks and

hand sanitizer for its employees, as well as for medical

workers.

Overtime is eschewed because putting workers on an extra shift

with a different crew exposes more people should someone become

infected. If a worker becomes ill, their entire team goes into

quarantine.

P&G, at all its factories including Albany, checks workers'

temperatures at the start of their shifts. Start times and lunch

breaks are staggered to avoid lines at the doors or people sitting

close on breaks. The cafeteria has no salad bar or open food, just

prepackaged options. Team meetings are generally held over video,

even if everyone is at the plant.

Mr. Patterson, the P&G plant veteran, said the hardest thing

is having to maintain distance from friends and family who are

struggling.

"In other times we could be there to console folks in their time

of need, really display that Southern hospitality," he said,

recalling the aftermath of the hurricane and tornado that hit

Albany. His wife, who is a furloughed nurse, is teaching their five

children at home since schools shut down.

Work, he said, is a consolation. "We've been able to deliver

more than I've ever seen us do before," he said. "Please let folks

know that Charmin is on the way."

Write to Sharon Terlep at sharon.terlep@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 12, 2020 12:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

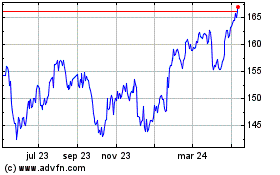

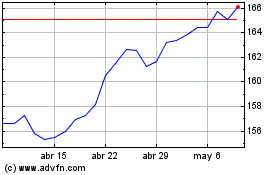

Procter and Gamble (NYSE:PG)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Mar 2024 a Abr 2024

Procter and Gamble (NYSE:PG)

Gráfica de Acción Histórica

De Abr 2023 a Abr 2024